Drop Rate Idea

introduction

Traditionally, in any RPG games, the drop rate was always fixed or modified by some internal “luck” variable (which the players could not see). This method had its pros and cons and I had an idea to improve this method for players who had bad luck.

my idea

My idea was that, for each drop from an enemy kill that didn’t drop, its drop rate would increase until the player would eventually get the item, after which the drop rate would reset. For example, in Terraria, the drop rate of Rod of Discord was 1 in 2500. With my method, the first kill would still be 1 in 2500 but the second kill would be 2 in 2500 and the 3rd one would be 3 in 2500. This guarantees that even a player with the worst possible luck could get it after 2500 kills.

I used Monte Carlo simulation to see how my method was when compared to the traditional method. I wrote a Python script and here was the code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random

def get_time(up, down, change):

up_backup = up

t = 0

while True:

t += 1

r = random.randrange(down)

if r < up:

return t

if change:

up += up_backup

def average(tries, up, down, change):

min1 = 2147483647

max1 = 1

total = 0

arr = [0] * 400

for i in range(tries):

v = get_time(up, down, change)

arr[v // 100] += 1

total += v

if v > max1:

max1 = v

if v < min1:

min1 = v

acc = arr[0]

for i in range(1, len(arr)):

acc += arr[i]

arr[i] = acc

if acc == tries:

arr = arr[0:i + 1]

break

plt.bar(range(len(arr)), arr)

plt.title('Line Plot Example')

plt.xlabel('X-axis Label')

plt.ylabel('Y-axis Label')

plt.show()

if change:

plt.savefig("a.png", dpi=600)

else:

plt.savefig("b.png", dpi=600)

print("total:", total)

print("average:", total / tries)

print("min:", min1)

print("max:", max1)

average(10000, 1, 2500, True)

average(10000, 1, 2500, False)

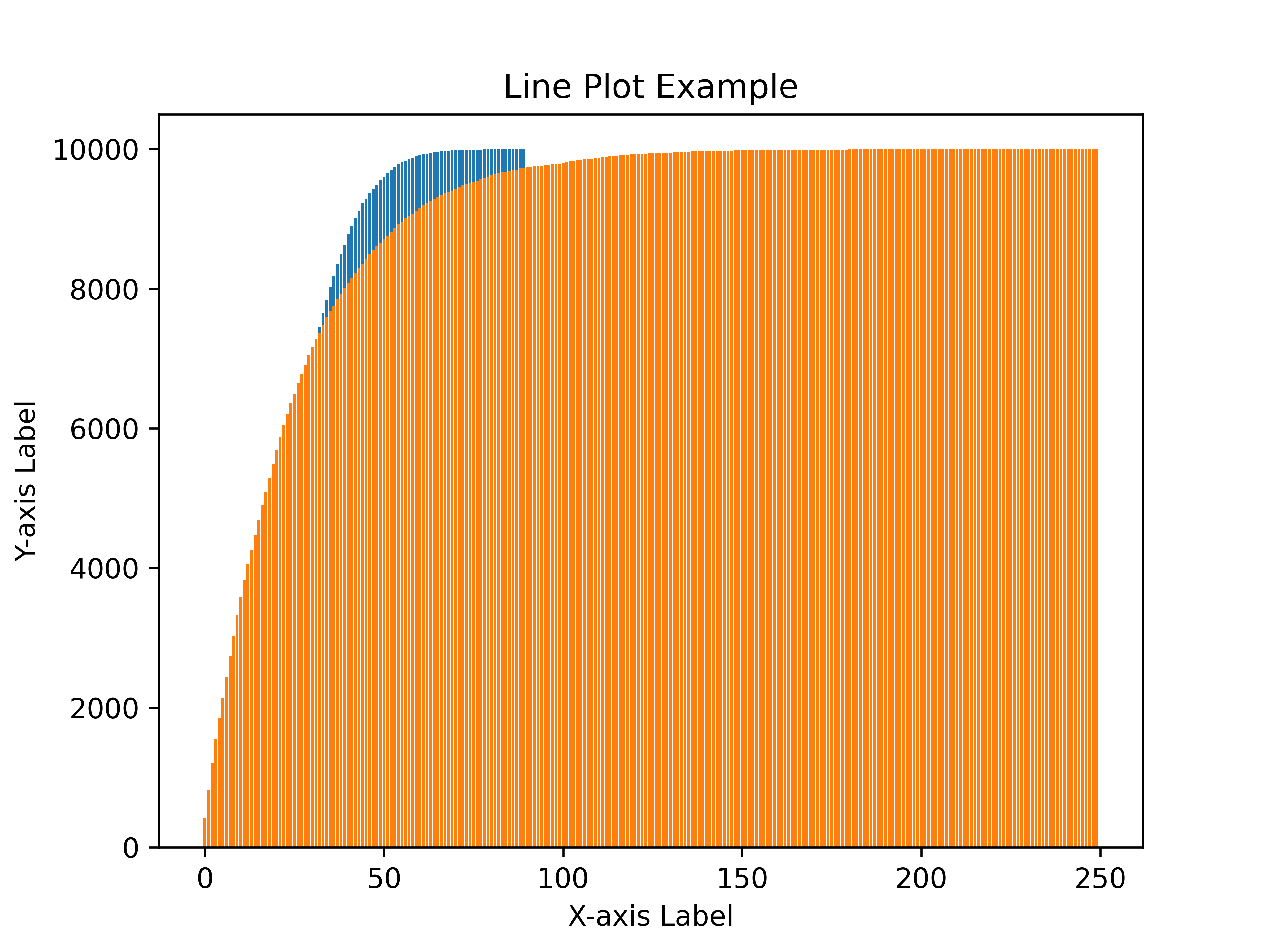

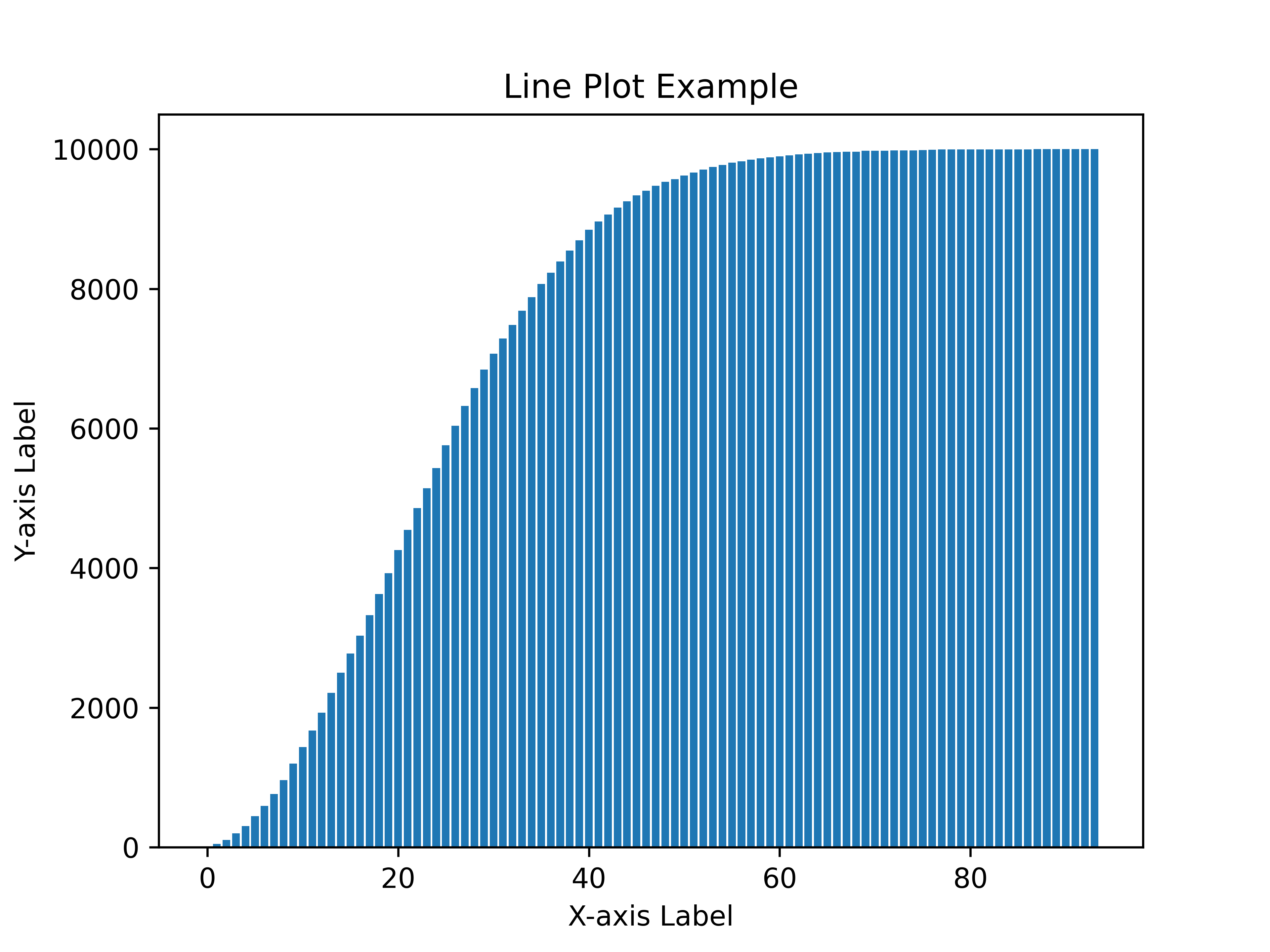

The resulting graphs looked like this (The x-axis represents how many kills are required to get Rod of Discord (divided by 100) while the y-axis represents how many players get their Rod of Discord when killing the corresponding amount of enemies.):

This simulation simulates 10000 players farming the same enemies until they got Rod of Discord. With the traditional method, on average, a player needed to kill 2500 enemies before they got Rod of Discord. This is expected. However, the worst case is staggeringly bad - in the simulation shown above, a player has to kill nearly 25000 enemies before they got Rod of Discord!

My method did a lot better, of course, because I literally increased the drop rate. However, the drop rate was way too good. On average, it only took 62 kills. even in the worst case, the player only needed to kill 226 enemies.

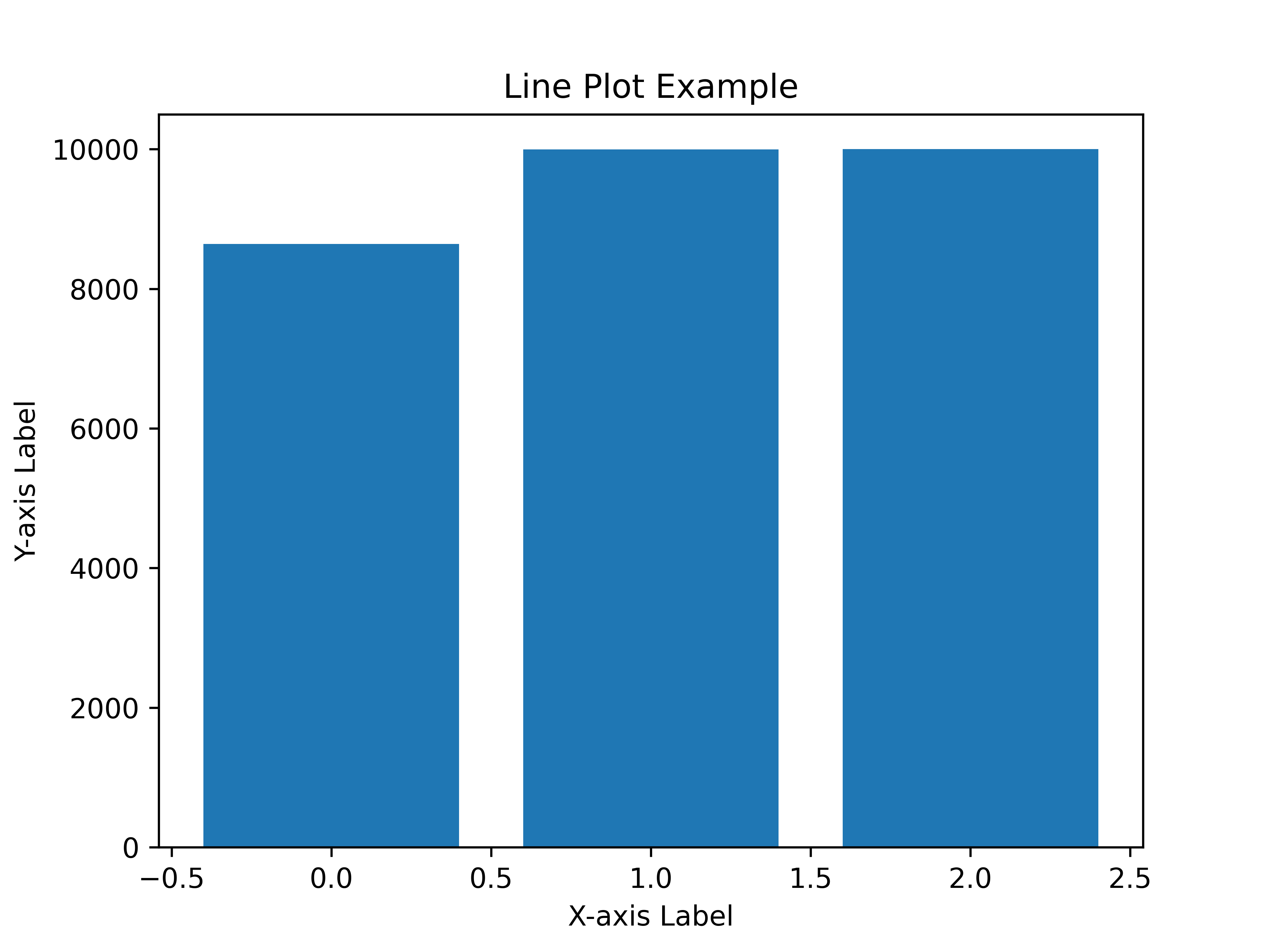

I adjusted the drop rate when using my method so that the average would match that of traditional methods. It turned out the drop rate had to be 1 in 4 million for the average to become 1 in 2500. Here is the new chart:

This does look a lot better. The average amount of enemies the players need to kill to get Rod of Discord was the same - 2500 enemies. But the worst case became only nearly 10000, which was a lot better than traditional method.

…However, there was one caveat. With the traditional method, if the player got their Rod of Discord from the first enemy, they’d consider themselves to be extremely lucky. With my method, it would rob away that feeling of happiness. However, if the player didn’t get theirs after killing 20000 enemies, they’d consider themselves to be extremely unlucky and get really frustrated with it. With my method, this could help alleviate that situation. My method would make the players experience roughly the same, while it’s good for saving the frustration of unlucky players, it would also rob the ecstasy feeling of the lucky players. I honestly wasn’t sure if it was a good thing.